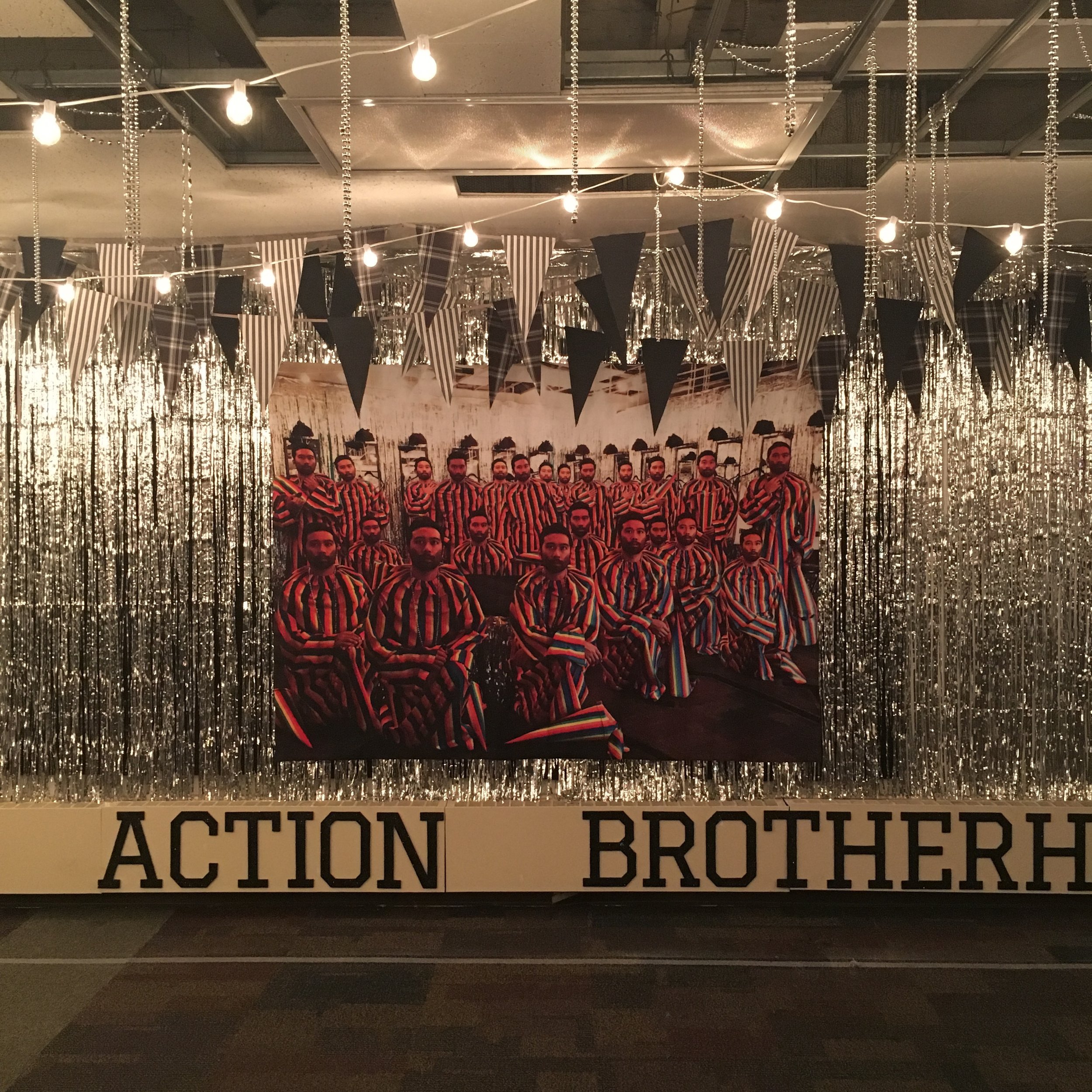

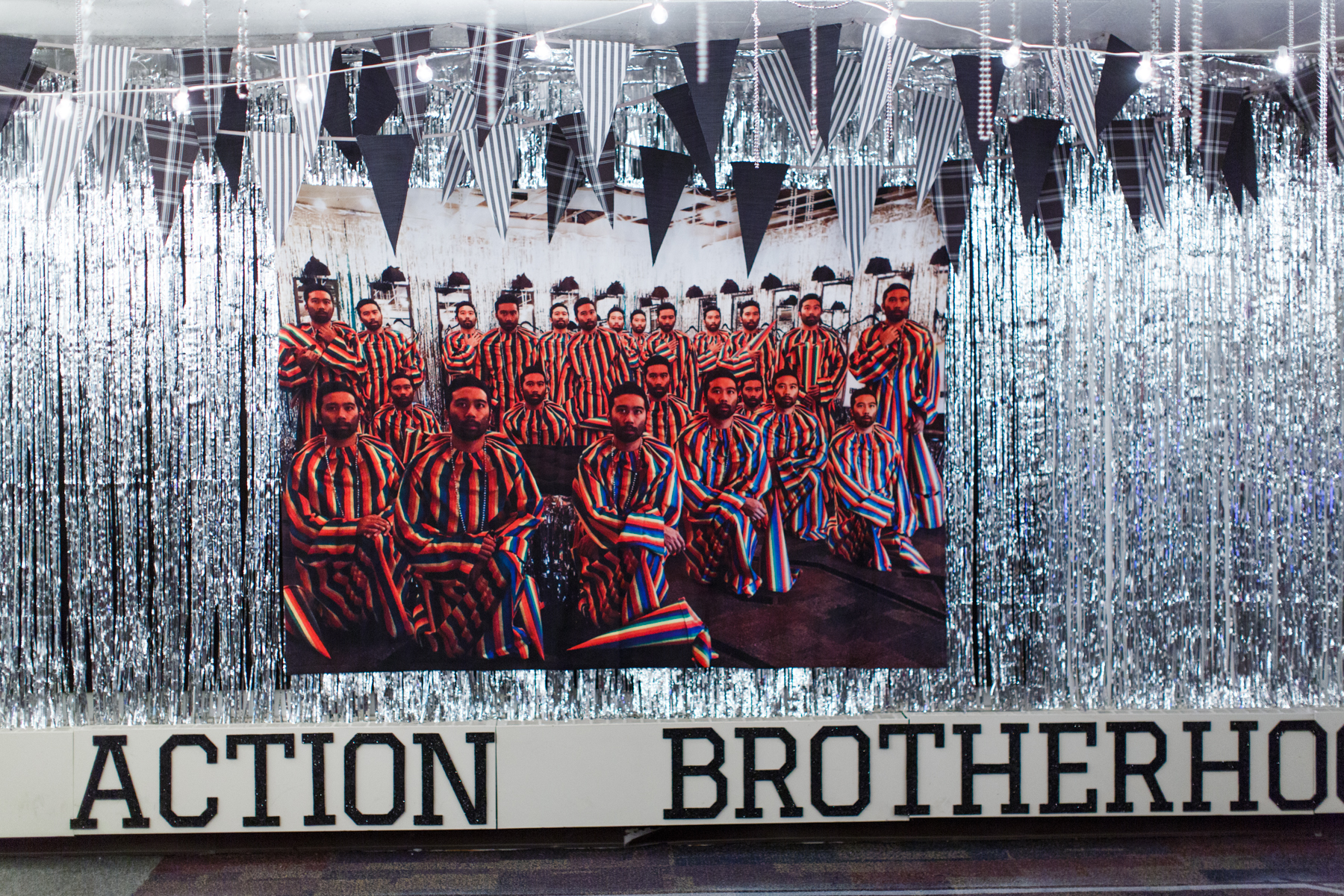

installation view of Society of 23's Locker Dressing Room

Society of 23's Locker Dressing Room

2017

mixed-media installation

Click the image above and experience a virtual walkthrough of the installation.

I live every day of my life in fear. The moment I wake up, I wonder what the day will bring me: another accident on U.S. 131, another hate crime against an innocent victim, another hurricane barreling through the country. I try to avoid the news and social media, but my interest in current events and pop culture is an addiction. I want to cherish each sunset that pours over this city of Grand Rapids I’ve called home since November 1, 2016, but the ongoing effects of the presidential election make it impossible. The threat of nuclear war and the rallies of white supremacists have aligned with my anxieties and I’m no longer certain as to what is real and what is imagined.

In 2008, I created the Society of 23 as a multi-media, long-form, and non-linear narrative that documented a mysterious brotherhood of 23 men – all played by me. As a former child actor, I was excited to perform again. As a former brother of a college fraternity, I was excited to create my own rituals and traditions. In 2011, I entered ArtPrize for the first time with the sculpture GayGayGay robe, the ritual robe of the Society of 23, which was exhibited at the Westminster Presbyterian Church. This year, I chose to explore the private history of the robe in its context within the walls of the brotherhood’s Locker Dressing Room.

This installation combines two sites of social engagement – a sports team locker room and a backstage theater dressing room. I’m inspired by the dramatic locker rooms of Division I collegiate sports teams, and the dressing room depicted on the reality television competition program RuPaul’s Drag Race. Both examples describe a complex definition of American masculinity that is inherent to each brother of the Society of 23, from conspicuous aspirations of physical strength and the becoming of the athlete, to subversive ideas of gender and the becoming of the performer. Two prominent examples of inspiration come to mind when I think about this artwork: Colin Kaepernick and other NFL football players peacefully protesting during the national anthem, and the album cover art for the Broadway revival of A Chorus Line.

On May 19, 2017, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu gave a special address at Gallier Hall before a fourth Confederate monument was dismantled in his city. He quoted former President George W. Bush’s remarks from the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on September 24, 2016, and stated, “A great nation does not hide its history. It faces its flaws and corrects them”. Much like history, signs and symbols are dynamic. With its origins during the Spanish Inquisition followed by its rebirth by the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, the image of the conical hat, mask, and robe is one such image that continues to evolve.

Symbols can change. They can become something different, like the appropriation of the ancient swastika symbol by the Nazi party, or the various cultural icons used by American sports teams like the Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Chiefs, and Washington Redskins, or even the commercialization of the ancient practice of yoga. The Society of 23’s uniform/costume is a “form of expression”. It is “an artistic creation that is both subjectively intended and objectively perceived” as a violent “symbol” of suffering(1). Several artists have worked with these images throughout history, including Francisco de Goya, Andres Serrano, and Santiago Sierra. These works of art reveal emotional narratives depicting hierarchies of power and the theater of identity.

Art has the power to tell stories and create meaning. The ritual robe of the Society of 23 appropriates this symbol of suffering, humiliation, performance, and spectacle. What the symbol becomes is still unclear. We do not yet know what the brothers of the Society of 23 do once they put on their uniform/costume, but we can find clues in the Locker Dressing Room that reference other works of art, including Andy Warhol’s Empire, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled light strands and beaded curtains, and Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle.

I wish I could exhibit a work of art for you today that didn’t revolve around pain or suffering. I wish I could hold my boyfriend’s hand in public without fear of ridicule or shame. I wish that a man wasn’t defined by how many beers he could shotgun or the number of sports he played in high school. But wishes take time to grant, so please stay tuned while I work on them. For now, the Society of 23 is a contemporary American tragedy. It’s a story filled with difficult themes to acknowledge and that take time to unpack. But like one of my favorite movies, Titanic, there is a love story somewhere here, if you choose to see it. “You must do me this honor: Promise me you will survive, that you will never give up, no matter what happens, no matter how hopeless, promise me now, and never let go of that promise. Never let go.”

(1)”Trump administration lawyers joined sides with a Colorado baker Thursday and urged the Supreme Court to rule that he has the right to refuse to provide a wedding cake to celebrate the marriage of two men. Acting Solicitor Gen. Jeffrey B. Wall filed a friend-of-the-court brief arguing that the cake maker's rights to free speech and the free exercise of religion should prevail over a Colorado civil rights law that forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation. ‘A custom wedding cake is a form of expression,’ he said. ‘It is an artistic creation that is both subjectively intended and objectively perceived as a celebratory symbol of a marriage.’ And as such, the baker has a free-speech right under the 1st Amendment to refuse to ‘express’ his support for a same-sex marriage, Wall argued.”